Filter

My Wish List

![]() Chalice Coral Care

Chalice Coral Care

Chalice Corals are a broad collection of corals that are loosely jumbled together. Several different genera of corals are represented ranging from Echinopora, Oxypora, Mycedium, and even Lithophyllon. As such, care requirements are going to be generalized more than other corals because these are very different corals that all get lumped in together.

Although their exact classification can be a murky topic, their impact in the reef aquarium hobby is crystal clear. Chalice corals are one of the most highly desirable large polyp stony corals in the industry. This is due in large part to the colors and patterns chalices are capable of expressing. High-end Chalices often have intensely fluorescent colors and can display striking patterns. My personal favorites look like glowing melted crayons.

![]() Location

Location

In terms of their distribution in the wild, chalice corals are found all over the Pacific. Given their broad distribution one would be led to assume that they are readily available in the hobby, but lately that has not been the case. At the time of this recording, there is currently an import/export ban in Indonesia and Fiji where many of these corals come from so most of the specimens available in the trade are being imported out of Australia.

![]() Lighting

Lighting

I recommend moderate lighting levels around 100 PAR. Most types of chalice corals are adaptable to different lighting intensities but the first priority should always be “don’t blow away corals with light.” It does not take very long to overexpose chalice corals that can lead to bleaching and a rapid decline in health. It is far better to provide substandard lighting intensity and slowly correct the situation by adjusting the light or placement of the chalice coral RATHER THAN accidentally blasting the coral with too much light and then trying to help it recover after it bleaches.

The other reason why I would not be in a huge hurry to go crazy on light is that for the most part, chalice corals are pretty consistent with their coloration. Sure there is always some degree of variability and the occasional outlier that CAN change their color in noticeable ways, but overall there is not a lot to be gained by messing with lighting. I would aim for moderate, consistent light and just let the coral adapt to the lighting conditions on its own.

One last point I will mention about lighting is bringing out fluorescence in chalices. Many species of chalice corals are highly fluorescent under actinic blue LED lights and are real show stoppers. Even if you are a die hard metal halide or t5 fan, you are missing out if you haven’t seen chalice corals under full actinic LED illumination. Consider getting just one inexpensive strip for late night viewing.

Low Light

Lighting is a loaded topic, so for a more in-depth discussion of lighting, please see our Deep Dive article.

![]() Water Flow

Water Flow

Like light, water flow is not something that I would go crazy with. Moderate water movement is recommended.

Too little flow and you run the risk of allowing detritus to settle on the colonies which creates dead spots. Several species of chalice corals naturally form a bowl shape and there has to be enough flow to sweep away anything that would otherwise settle in the middle.

Too much flow and you run the risk of having the coral fall off the rock work. Their plating shape once again plays a role because if there is a lot of flow, the colony acts like a sail and can lift it off of the rocks and either face down in the substrate or worse yet onto another coral.

![]() Coral Aggression

Coral Aggression

Chalice corals are aggressive. Only a few varieties extend sweeper tentacles, but any contact by the body of a chalice coral with another coral is going to be highly volatile.

The video below provides an overview of the different manifestations of coral aggression and ideas on how to mitigate some of the risks inherent in keeping corals in small quarters.

![]() Feeding

Feeding

Chalices are considered photosynthetic corals meaning they have a symbiotic relationship dinoflagellates living in their flesh called zooxanthellae. Strictly speaking, the zooxanthellae are the organisms carrying out the actual photosynthesis but the coral animal benefits by accessing the byproducts of their photosynthetic activity, namely the simple sugars that are produced.

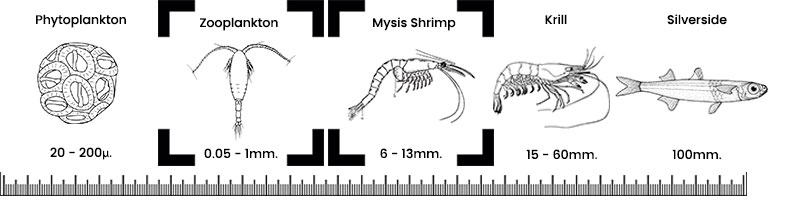

Although chalice corals derive much of their nutritional needs from the byproducts of photosynthesis, they are also capable feeders. Here at Tidal Gardens, we have tried feeding chalices a number of different types of food ranging from frozen foods to pellet foods. Chalices do not have pronounced polyp extension so their feeding response can be difficult to monitor. Typically these corals utilize a mucus coat to capture food and slowly draw it into their mouths which can be seen during feeding time lapses.

Feeding can be hit or miss though, so it is something you will have to play with and figure out what foods to feed and which types of chalices like what.

![]() Propagation

Propagation

Chalice corals overall are a great candidate for long-term sustainable aquaculture.

Some varieties of chalice corals naturally propagate better than others but I have a couple tips that might help. The times that I see hobbyists struggle to propagate this coral it is usually for two reasons.

The first is underestimating what makes them an aggressive coral. The mucus and other chemicals that are released by cutting them persists on the tools used for propagation. Often times these tools are used to cut several different chalices in the same fragging session. By using the same tools on different kinds of chalices, you might get some undesirable interactions. I encourage people cutting chalices to try and clean everything in between cutting different species. That means cleaning off bone cutters, saw blades and making up new water for the saw each coral.

The second problem with propagating chalice corals is they can be a challenge to glue down to a new substrate. It can be a frustrating process of cutting perfect little frags and to have them all dislodge the next day because the glue failed.

There is no perfect method for getting them to stick down, but one thing that can help is to use a generous dollop of gel superglue and immediately spray it with an instant set product.

![]() Summary

Summary

Chalice corals are one of the most highly desirable large polyp stony corals in the industry. They are not particularly difficult to care for, but because the category includes over ten Genera of corals, optimizing tank conditions for a particular specimen is going to require some degree of experimentation. Enjoy the process reefers!