Filter

My Wish List

![]() Alveopora Coral Care

Alveopora Coral Care

This article is all about Alveopora. Alveopora is a large polyp stony coral that has a beautiful flower-like appearance. They aren’t the most rare coral by any stretch, but it is far more common to see their close relative Goniopora. Like Goniopora flower pots, Alveopora don’t have the best reputation for survival however that reputation may or may not be deserved.

Let’s cover what the differences between Alveopora and Goniopora. First, both corals have round stony skeletons from which a bouquet of stalks extend from. Where they differ is the number of tentacles on each polyp. Alveopora have 12 tentacles on each polyp while Goniopora have 24. That is the quickest and easiest way to differentiate the two.

Second, Alveopora may be a hardier specimen than Goniopora. Goniopora for ages have developed a poor track record for survival. There are about 20 or so species of Goniopora and some are actually quite hardy, but for years there are varieties frequently imported that did not fare well. A typical pattern would be to get a nice fully fleshed out colony and it would seemingly thrive for about 6 months. After that period however it would take a sudden downturn and be dead within 48 hours. Today, there are some very robust species of Goniopora available but the stigma has stuck and even covers similar-looking corals such as Alveopora.

![]() Location

Location

Alveopora are found in the islands of the Indo-Pacific including Fiji, Tonga, Solomon Islands, and the Great Barrier Reef.

![]() Lighting

Lighting

In terms of lighting, Alveopora seem to do well in a variety of intensities. Some corals are very light demanding and can change color dramatically under different intensities or different spectrums, but Alveopora tend to maintain a consistent appearance. I would recommend finding a spot in the tank where the coral would receive a middle of the road intensity of around 50-100 PAR. There is much greater risk when providing too much light rather than too little, so if you are going to miss the mark, go for less light.

Low Light

Lighting is a loaded topic, so for a more in-depth discussion of lighting, please see our detailed lighting video.

![]() Water Flow

Water Flow

As for water flow, I like to see Alveopora in medium to high flow. Again this coral is tolerant to a wide range of flow conditions, but seeing a large colony of Alveopora blowing in the current is a wonderful sight. I wouldn’t even worry about putting it into high flow because the coral itself will make it obvious if you’ve overdone it. Alveopora is very reactive to anything bothering it for example, if you pick it up, all the polyps will quickly retract. If you have placed the colony in too much flow, just look at the coral. If the polyps are out and swaying, it’s likely fine.

![]() Water Chemistry

Water Chemistry

Like with any stony coral, you will want to make sure the tank’s calcium, alkalinity, and magnesium levels are all where they should be. Alveopora are not a super fast growing coral compared to some fast growing SPS, but for a large polyp stony coral, they are pretty fast. In that sense, they rely on a steady uptake of these major elements to keep growing.

I’ve made separate videos about each of these chemical parameters that are worth checking out. Let’s start with Calcium. Calcium is one of the major ions in saltwater. In most healthy reefs, the calcium level hovers around 425 parts per million (ppm).

Alkalinity is a little more difficult to explain than calcium. It is not a particular ion, but can be thought of as the buffering capacity of saltwater. Buffering capacity is the amount of acid required to lower the pH of saltwater to the point bicarbonate turns into carbonic acid. In layman’s terms, higher alkalinity levels equate to greater chemical stability in our reef tanks. In practice alkalinity tends to be the parameter that fluctuates the most of the three and is the one that needs the most babysitting. In the wild, the alkalinity of the water is around 8-9 dkh.

One quick note about adjusting calcium and alkalinity: it can be a little tricky because of how they interact. For example, if your reef tank had a calcium level of 300ppm when you desire a value closer to 400ppm, you could theoretically add a calcium supplement to boost it. Unfortunately, reef aquarium chemistry is dynamic and solutions to chemistry issues are rarely that straightforward in practice. Addition of a calcium supplement in this manner often comes with a corresponding fall in alkalinity levels.

This see saw effect between calcium and alkalinity stems from how the two ions interact with one another. The two ions combine to form calcium carbonate and fall out of solution, thus lowering both levels.

If you are experiencing this in your systems, the possible culprit with calcium and alkalinity instability is Magnesium. It may seem counterintuitive that the solution to calcium and alkalinity imbalances is to elevate magnesium, but the three ions interact regularly.

Magnesium is very similar chemically to calcium. It can bind up carbonate ions thus increasing the overall bioavailability of alkalinity compounds in the water. So again if you find that no amount of tweaking calcium and alkalinity directly is helping, you may want to make sure it is not your magnesium level that is in fact low.

Once the colonies start growing, keep an eye out on these parameters and remember that consistency is what to shoot for. Here at Tidal Gardens we try to keep water chemistry close to natural sea water levels. People like to keep their levels slightly higher than NSW because it provides a slight buffer in the event of a dip, but it’s more of a crutch because again consistency is the goal rather than a particular value.

In the video below, I cover three different aquariums that utilize different techniques to manage their chemistry.

![]() Feeding

Feeding

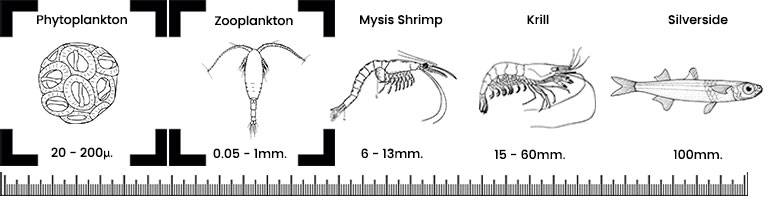

In addition to lighting, coral get nutrients from feeding. When it comes to proactive spot-feeding, I’m on the fence. Alveopora would likely benefit from regular feedings but they may be a challenge to feed. What we have done recently here is make a mix of several commercially available powdered plankton foods and feed them all together to all of our corals. Basically the shotgun approach to feeding. Having said that, it’s important to not overfeed because the downside to a nutrient explosion far outweighs the benefits of feeding, so don’t over-do it.

For finicky corals such as Alveopora, it can be difficult to see if they are actually consuming the food or not. I always look for this pogo-stick behavior where one of the polyps will quickly retract and then slowly re-extend. I’ve heard anecdotally that is a feeding response, but I am not sure. I’ve seen similar behavior in Goniopora. I’m hoping that it’s a feeding response and not a sign of the food aggravating them.

![]() Propagation

Propagation

This genus for the most part has been propagated extensively in captivity and is an excellent candidate for aquaculture. It is reasonable to believe that a sustainable harvest can be achieved in time. One observation I’ve made with Alveopora is they seem to heal from propagation very quickly. Just a few days after we cut a colony, I can see that the cut edge is growing back.

![]() Summary

Summary

So who is this coral for? I see this coral going into a mixed reef or stony coral dominated tank that wants to recreate the movement of soft corals but using stony corals. Corals such as hammers, torches, and frogspawn as well as elegance corals all fit into this aesthetic. Alveopora complement these LPS corals well because they come in pastel colors that aren’t often seen such as bright pink.

Ok, that just about does it for Alveopora. Until next time, happy reefing!